Louis Pasteurs risky move to save a boy from almost certain death

Early in the morning of July 4, 1885, a “mad dog” attacked a 9-year-old boy from Alsace, France. His name was Joseph Meister. The vicious and crazed dog proceeded to throw the boy to the ground and bite him in 14 places, including the hand, legs and thighs. Some of the wounds were so deep that he could hardly walk. Twelve hours later, at 8:00 in the evening, a local doctor named Weber treated Joseph’s most serious wounds by cauterizing, or sealing them, with searing doses of carbolic acid, in and of itself a horribly painful process.

Beyond the bites themselves, the boy’s mother feared her child had contracted rabies, which was widely feared as a near certain path to death. Despite the relative rarity of rabies in 19th century France, the shocking symptoms and grisly power to kill captured that nation’s attention, just as many newly emerging contagious events — such as SARS, Ebola and Zika — have done in the United States today.

Mrs. Meister took Joseph straight to Paris because she heard that a scientist there was working on a cure for rabies. Once there, she made inquiries on how to find this man and was told to go directly to the laboratory of the now famous microbiologist, Louis Pasteur.

Despite the relative rarity of rabies in 19th century France, the shocking symptoms and grisly power to kill captured that nation’s attention, just as SARS, Ebola and Zika have done today.Pasteur was, indeed, hard at work developing a rabies vaccine, using dogs as his experimental subjects. Up until now, however, he had not administered the vaccine to a human being. In reality, he could not do so legally because he was not a medical doctor; his doctorate was awarded for dissertations in chemistry and physics. More importantly, he could not yet prove that his rabies vaccine was effective — as opposed to useless or even harmful — for humans.

Pasteur was so taken by the boy’s plight that he consulted two physicians, Alfred Vulpain and Jacques Grancher at a weekly meeting of the French Academy of Sciences. They, too, were struck by the need to do something, and to do it fast. Pasteur later reported, “Since the death of the child appeared inevitable, I resolved, though not without great anxiety, to try the method which had proved consistently successful on the dogs.”

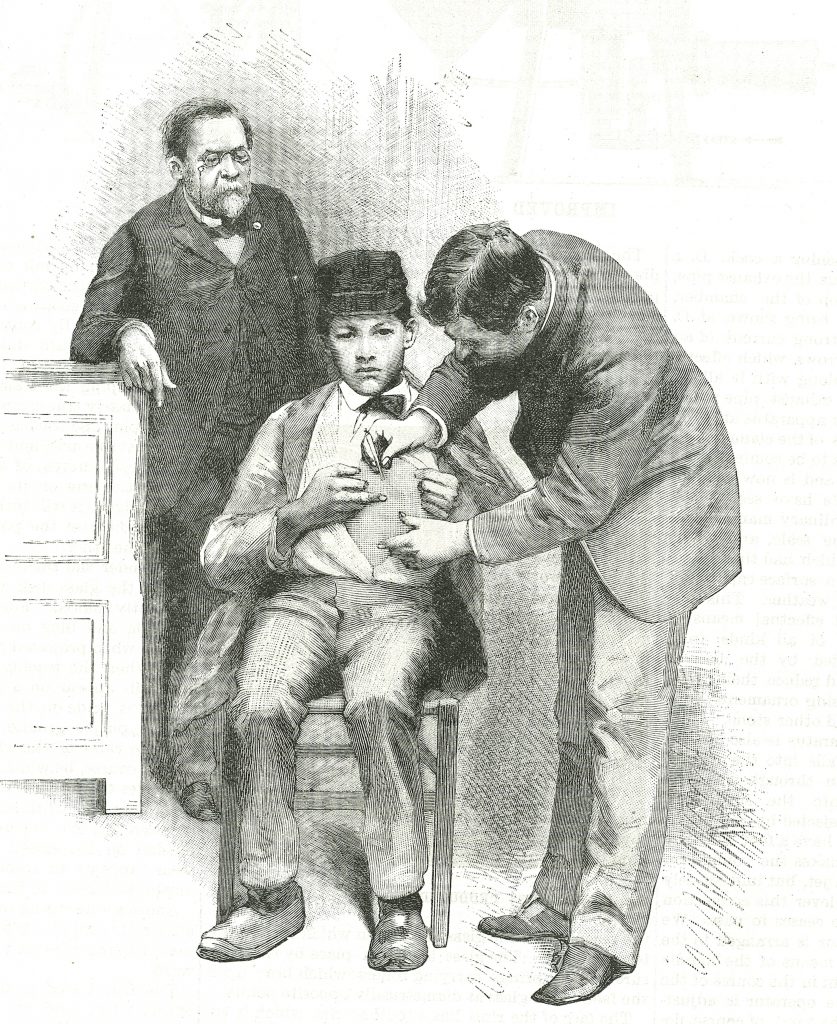

Pasteur escaped the medical license dilemma by having his medical colleagues present when the vaccine was first administered on July 6, 1885, some 60 hours after the initial dog attack. Mrs. Meister expressed little concern over the potential dangers of the experimental vaccine because she was so fearful that her son would die and she readily gave Pasteur her consent.

The first injection was made in a fold of skin covering the boy’s right upper abdomen. Over a period of three weeks, Joseph was given 13 such inoculations. Pasteur monitored the virulence of each dose by first injecting them in healthy rabbits to insure the vaccine did not cause rabies. Each dose came from progressively more rabid rabbits. At the end of the treatment course, Joseph was inoculated with an especially virulent rabies virus from a mad dog. Nothing happened! Pasteur was pleased to announce, thanks to his vaccine, Meister had developed an immunity to rabies virus.

The rest of Louis Pasteur’s remarkable career as a world-changing scientist has been well documented in a shelf of books and articles about him.

But whatever happened to Joseph Meister?

He fully recovered from the dog attack, for starters. Louis Pasteur later hired him to work as a concierge at the Institut Pasteur, his deluxe laboratory where some of the most important discoveries elucidating infectious diseases were made. There Meister happily worked for several decades until the second World War broke out.

On June 24, 1940, 10 days after the German army conquered Paris, a 64-year-old Meister took his own life. For many years, the popular legend of Meister’s death was that he committed suicide rather than allow (or watch) the Nazi invaders to pillage Pasteur’s crypt.

Recently, however, this story had been debunked, or at least augmented with more accurate facts, thanks to two intrepid researchers named Héloïse Dufour and Sean Carroll.

Using the diary of Eugene Wollman, the head of the institute’s bacteriophage laboratory at this time, other archival sources, and interviews with Meister’s granddaughter, Dufour and Carroll discovered that Meister killed himself by turning on a gas stove, rather than a self-inflicted gun shot as has often been reported. In fact, he did not take his life out of an obligation to protect Pasteur’s remains. Instead, he was despondent over his wife and children. They had fled Paris a few weeks earlier to escape the Nazi bombing, and Meister somehow got it into his head that the Germans had killed them.

Here’s the most striking irony of this tragedy: His very much alive wife and daughters returned to Paris later that very day only to find Joseph dead.

The story of Meister standing guard over the coffin of the man who saved his life is just a myth, but a heroic myth, nevertheless.

What has never been in doubt, however, is the fact that on July 6, 1885, Joseph Meister made medical history.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eYmq6twMdoo6itmah6sa3SrZyuqqNiv6q%2FyrJkpqemmnq1u4ysmK%2BdXZZ6o7vYZp2rp51irq25zqyrZpuVp8Gitc1mm56ZpJ0%3D